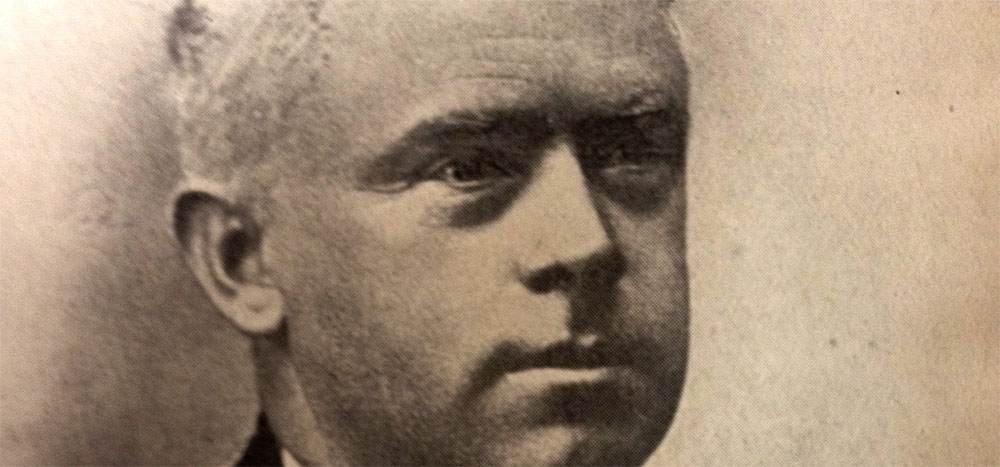

Rev. Dr Richard Henebry

Rev. Dr Richard Henebry was born in Mount Bolton, Portlaw, in the east of County Waterford on 17 September 1863 and passed away on St Patrick’s Day, 17 March 1916. The multiple binaries of his life lived – local and national, music and language, intellectual and practitioner, priest and secularist, among others – are the bedrock on which he built his philosophy of Irish culture and identity. Though Henebry was academically first and foremost a linguist, the connection with Henebry through this project is a musical one.

The society in which Henebry was reared was still reeling from the effects of the Great Famine (1845-1849), and his early years were a period of radical change in land ownership, tenancy and acquisition in rural Ireland. As Julian Walton notes, Henebry was embedded in Irish traditional cultural life from birth (Aquila 1997: 36). At a time when the Irish language was in steep decline, Henebry learned Irish primarily from his mother, a fluent speaker and a living repository of folklore and stories.

It was also from his mother that he drew his musical talents and interests. He played fiddle himself and his siblings were also musical. In particular, his brother John (he was also known as Jack or Eoin), is remembered for his uilleann piping and song making. Francis O’Neill described Henebry’s fiddle playing as ‘a revelation’, though he then qualifies his praise somewhat by writing ‘had his practice kept pace with his knowledge of the subject, our champions would be feeling uncomfortable’ (O’Neill, 1910: 47-48). What is indisputable, is that Henebry’s passion for Irish traditional music, which was instilled in his childhood, continued throughout his adult life.

It was also from his mother that he drew his musical talents and interests. He played fiddle himself and his siblings were also musical. In particular, his brother John (he was also known as Jack or Eoin), is remembered for his uilleann piping and song making. Francis O’Neill described Henebry’s fiddle playing as ‘a revelation’, though he then qualifies his praise somewhat by writing ‘had his practice kept pace with his knowledge of the subject, our champions would be feeling uncomfortable’ (O’Neill, 1910: 47-48). What is indisputable, is that Henebry’s passion for Irish traditional music, which was instilled in his childhood, continued throughout his adult life.

The late nineteenth century was a crucible of cultural nationalism, which was most vibrantly expressed in the language revival and in an explosion of literature both in the English and, to a lesser extent, in the Irish language. However, there was also an accompanying revival of traditional arts practice. The Gaelic League, though primarily an Irish language revival organisation, was also centrally involved in providing platforms for traditional music and dance through competitions and festivals (such as Oireachtais and Feiseanna), as well as establishing the céilí dance format as the sine qua non of Irish traditional social dance. The turn of the century also witnessed the establishment in Cork and Dublin of the first piping clubs, which provided vital life-support for uilleann piping throughout the twentieth century.

Henebry’s view of Irish traditional music – as an art which was aesthetically and culturally valuable, but under threat – was shared by those involved in these contemporary organisations. Furthermore, his goal of arresting that decline, by whatever means were at his disposal, informed his interest in recording and writing about these traditions.