The Henebry Family

The townland of Mount Bolton (Barr a’ Bheithe or birch summit) backs onto Lord Waterford’s Curraghmore estate, looking down on the river Suir. Willie Power, a descendent of Henebry, contends that the Henebrys, were resident in the area by the 1740s, and possibly even before that (interview, 9 September 2011).

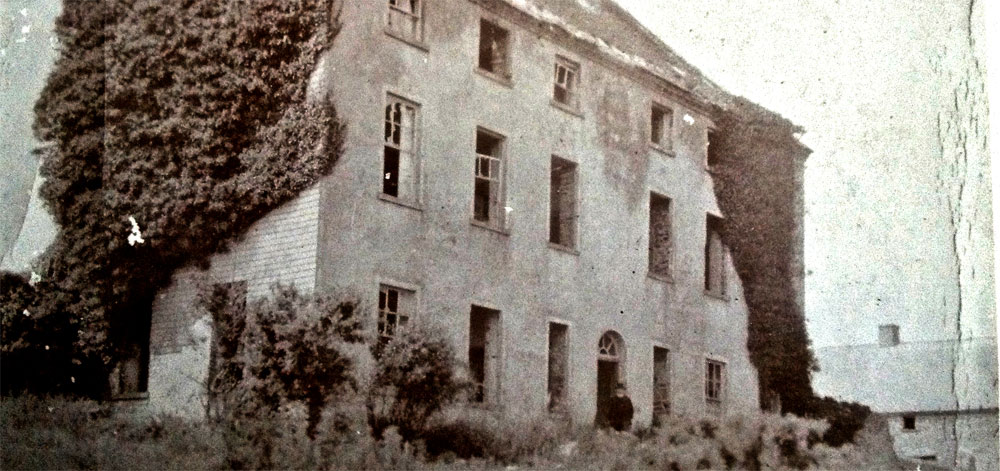

In the mid-nineteenth century, two Henebry brothers are registered as land owners in Mount Bolton and tenants of Jane Bolton, the absentee landlord of the Mount Bolton estate. The Boltons had not occupied the manor house for at least a century and Pierce Henebry, Dr Richard Henebry’s father, together with his family, lived in the ‘big house’ of the Bolton estate.

This was Richard’s childhood home, looking down on the sweep of the river Suir, surveying much of the Henebry’s own land. Jack Henebry, Richard’s brother describes a pastoral idyll in his political commemorative ballad ‘Mount Bolton’,

Jack Henebry – Piper

‘Now in my lonely fancy still appears,

The happy vistas of my youthful years,

The dear old house festooned in ivy wreath,

The lawn, the wood, the gliding Suir beneath,

The dear old house, my youth’s beloved resort,

Seat of my childhood plays and boyhood sport’

When Pierce Henebry’s lease expired in the mid-1880s, a summary eviction notice was issued. The eviction at Mount Bolton saw Pierce, his wife Ellen Henebry and their remaining children seek refuge in the very modest dwelling of one of their own previous tenants, Dicky Bolton (or, his given name, Richard Whelan). The manor house was never occupied again following the Henebrys departure though Philip remained in Mount Bolton, and indeed his descendants are still working that same land. In Jack’s lyrical song words, which echo the earlier ‘Cill Chais’ in many ways,

‘Thus every charm my native home possessed

With blissful hours my happy boyhood blessed

But times have changed, where once abundance reigned

The straits on want have visited remained’

And he goes on to say

‘And oh! My home, that amid prevailing blight

Thy fate was cast to crouch’ neath alien might’

Shortly after their eviction from Mount Bolton, Pierce Henebry and his remaining family moved into the town of Portlaw, initially to William St, and not yet to their final destination in Brown St.

Richard Henebry (he used Risteard de Hindeberg as the Irish translation) was the fourth of six children born to Pierce Henebry and his wife, Ellen (nee Cashin), all between 1860 and 1868. Ellen’s homeplace was across the river in Burnt Court, Clogheen, Co. Tipperary and it was from the Cashin side of the family that the music came through to the Henebry children. Henebry claimed it was through his mother that he also acquired his native tongue, a claim supported by Julian Walton (Aquila 1997). There was a tradition of clerical service in the family. Pierce had a brother, Robert, who was a priest, and a cousin in Philip’s branch of the family was a priest in New York. Several of Richard’s sisters became nuns and other cousins, inter-generationally, also joined the clerical ranks.

Following his primary education in Carrickbeg, Clonmore and Portlaw, where he was an impressive student, he spent two years doing classical studies. At the age of 21, he entered St John’s College in Waterford to follow the priesthood, where Canon Patrick Power was among his contemporaries. Such was his intellectual prowess that he won a scholarship to finish his studies in Maynooth. Accounts of Henebry invariably tell of his contrariness and obstinacy, and his obdurate character. As Canon Sheehan described it, ‘The combative element in him was abnormally developed’ (Catholic Bulletin, May 1916). He graduated in 1892 from All Hallows, not Maynooth as planned, due to an altercation with one of his superiors. He continued to agitate against those who positioned themselves in authority over him throughout his life.

Henebry briefly served on the English mission before he was offered the appointment of the inaugural Chair of Celtic Studies at Catholic University in Washington in 1895. The Ancient Order of Hibernians, the Irish-American Catholic organization, had funded the chair to the tune of $50,000 and Henebry was proposed by classmates Canon Sheehan and Fr Hickey for the appointment. Hickey notes in a letter to Fr Muiris Ó Faoláin that he and Sheehan had lobbied for Henebry (Mount Mellery, MS8, 41). In order to fully prepare for his appointment Henebry was given special leave to go to Germany to study, again with effective lobbying on his behalf by Hickey and Sheehan. He studied for his doctoral degree in Celtic philology in Freiburg and Greifswald with acclaimed Celticists Thurneysun and Zimmer. As always, Henebry’s wry reflections on his own behaviour are entertaining. He said of his friendship with Zimmer ‘Our normal intercourse was a series of ructions’ (Beatháisnéis, available at http://www.ainm.ie/).

He took up his appointment at Catholic University in Washington in 1898 only to be relieved of his duties within two years. Though he was suffering from ill-health (Irish Times, 6 November 1909), Henebry had also run foul of his colleagues in Washington. A diagnosis of tuberculosis by his London specialist resulted in him making his way to a sanatorium in Denver, Colorado for recuperation (Walsh and Foley, ‘Fr Peter Yorke, Irish-American leader’, Studia Hibernica 1974). While there, he developed curious habits which he retained throughout his life. In a fond obituary, Canon Sheehan recalls that following his sojourn in Denver, Henebry refused thereafter to wear overcoats or hats, and often slept in tents outdoors. Shoes, he thought, were antithetical to nature (Beatháisnéis). Various dioscesan appointments followed within Waterford and Lismore, before he put his name forward for the Chair of Irish Language and Literature at UCC in 1909, again an inaugural position.

Henebry remained at UCC until his death in 1916, but it was not a wholly satisfying appointment. His efforts to embed his model of Irish language teaching in the university were met with resistance, from students and others. His efforts to establish an archive of Irish traditional music also failed to be realised, and his ill-health compromised his own ability to achieve these objectives. During his lifetime, Henebry was recognized as a leading linguist, and his works on the Déise dialect of Irish contributed to an expansion of the academic field. Pedagogically (and perhaps culturally) an enduring part of his legacy was his role as a teacher at, and supporter of, Coláiste na Rinne, in An Rinn gaeltacht, Waterford (established in 1905). Henebry’s contribution included language instruction, and he taught traditional music to any students who were interested. Upon hearing the minstrel piper James (Jem) Byrne play in Mooncoin, Co. Kilkenny in 1904, he arranged to bring him to class to play for his students. Henebry relished his role as a contributor to various papers and periodicals, however the longest of his musical works published during his lifetime was a booklet, Irish Music: Being an Examination of the Matter of Scales, Modes and Keys with Practical Instructions and Examples for Players (1903) (available at http://www.itma.ie/). His analytical monograph, A Handbook of Irish Music (1928), published by University College Cork, appeared posthumously and was edited by Professor Tadhg Ó Donnchadha (1874-1949), Henebry’s successor in the Department of irish at UCC. The Handbook provides a comprehensive exposition of his musicological theories regarding Irish traditional music.